In my work at Cogent Legal, I have the opportunity to help attorneys develop their presentations and to create visuals that will help inform and persuade. In this post, I'll share some insights that I've gathered from going to court myself and from helping other litigators get ready for court.

This article won the LitigationWorld Pick of the Week award. The editors of LitigationWorld, a free weekly email newsletter for litigators and others who work in litigation, give this award to one article every week that they feel is a must-read for this audience.

It is ironic—as a litigation consultant, I write opening statements and closing arguments much more frequently than I did in my 16 years of litigating. I now get involved in a case at the fun part, past the discovery phase, at the eve of trial or mediation when it must all come together for presentation to a judge or jury.

In my work at Cogent Legal, I have the opportunity to help attorneys develop their presentations and to create visuals that will help inform and persuade. In this post, I’ll share some insights that I’ve gathered from going to court myself and from helping other litigators get ready for court.

It is never too early to start thinking about your opening and closing. Although you may be busy today, you will be even busier as trial approaches, so start now. Keep a file (paper or electronic) with thoughts about opening and closing, and update that file often as you go through the case. As a litigator, my firm often participated in “beauty contests” where we would pitch a client to get a case after we had done an initial analysis. One reason that we won many of those pitches is that we would develop for the client a strategy for the entire case, including what we planned to argue in closing argument and why that argument gave the client the best chance of winning. Knowing what you intend to say in closing will focus you on what you need to do each day as you develop your case.

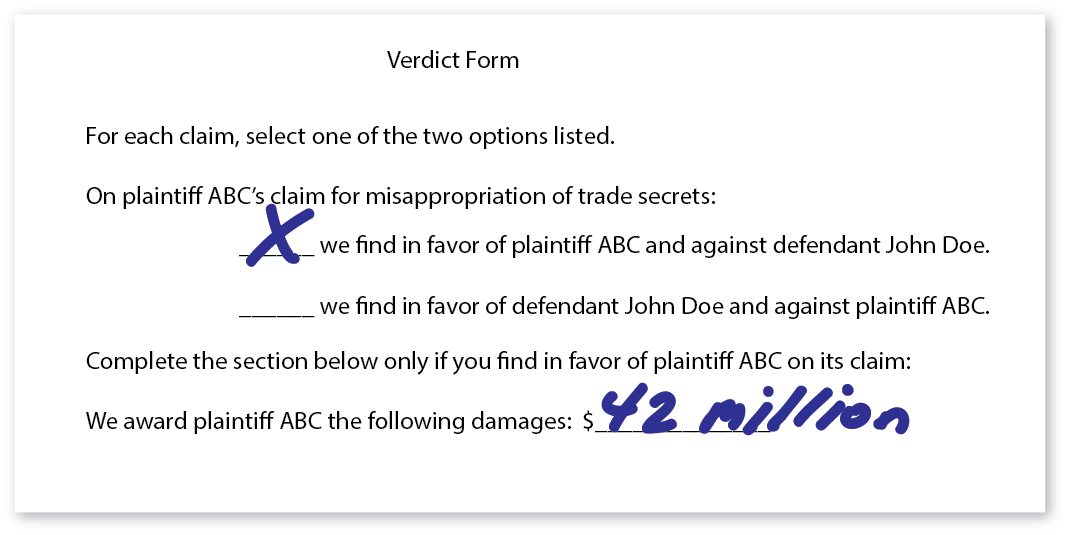

You need to give the jury a story with themes that organize and make sense of the evidence they will hear in trial. Identifying those themes early in the case will help you develop the evidence in discovery that will support the theme at trial. A former law partner of mine recently won a breach of contract and fraud trial using themes of (1) a deal is a deal; and (2) plaintiff was greedy. His opening, closing and his witnesses emphasized the care with which the deal had been negotiated, that plaintiff agreed to the deal, and how much money plaintiff had already made from the contract. These themes resonated with the jury as reflected in the verdict.

Understand your jury instructions early in a case, and use the instructions to identify your themes, and to structure your opening and closing. The jury will hear the jury instructions just before deliberations, and they will use those instructions in the jury room to evaluate your case. Your closing should guide the jury as to how your themes, the evidence and the jury instructions fit together and require a verdict for your client.

Cases should go to trial only when there is a real dispute in which the jury could go either way. In identifying your themes, think carefully about the most appealing arguments and evidence your opponent will present, and then think about how to counter those arguments and evidence. In your opening and closing, give adequate time and coverage to your opponent’s arguments and evidence. If you can, let the jury know that this is not a “two ships passing in the night” situation where the sides argue past each other. Rather, give the jury an understanding of what the other side says and why it should be rejected in favor of your client’s position.

“I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.” Blaise Pascal, The Provincial Letters, Letter XVI.

Your jury will never understand, nor care, as much about your case as you do. The jury’s time and attention is valuable and is limited, and you need to respect that by moving quickly for them and making your points clearly and succinctly. You may have lived with your case for years as it went through pleadings, discovery and motions, and your team likely understands every nuance of the case. You may have seven reasons why you should win a particular argument. However, in opening, closing, and the presentation of your evidence, you must make hard choices to simplify and edit. Weaker and confusing arguments should be jettisoned, and much of the detail must be left on the cutting room floor.

At Cogent Legal, we often help attorneys with this process of distilling and simplifying. For example, trial teams often ask us for timelines with many more facts than can fit on a display. We’ll help with suggestions for combining, editing, and/or breaking an argument down into simpler pieces that build over time for the jury.

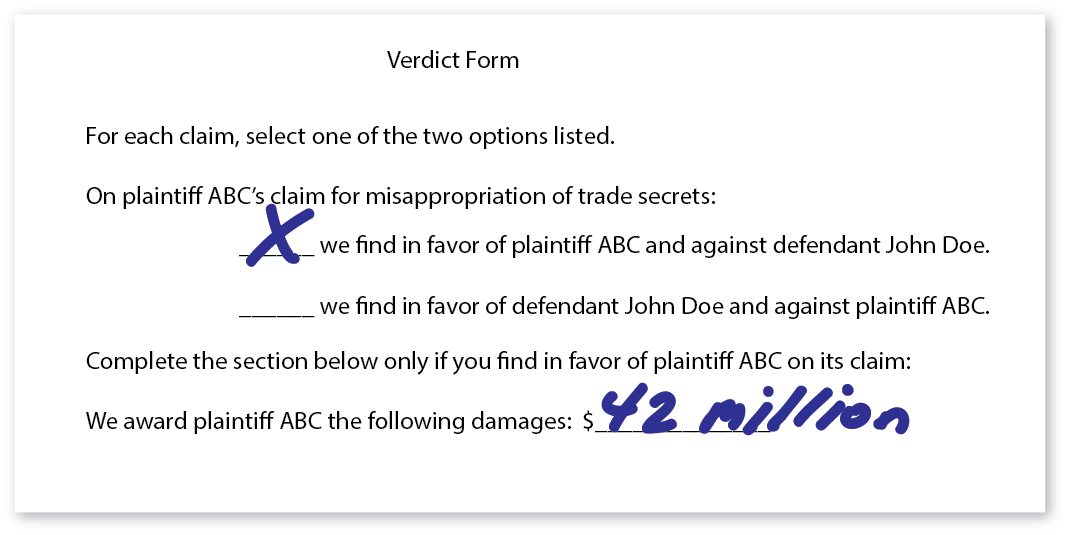

You can explain complicated facts to juries, but you should first consider if you can simplify. If you decide the complicated is needed, then think about how to build a foundation for the jury so they can understand step by step and by analogy or comparison to things they already understand. (For more on these topics, check out these earlier posts: Timeline Design for Litigation: When to Use a Static Timeline and Analogy, Illustration, Animation and Simplicity: A Lesson for Trial Graphics.) Below is an example of a graphic designed to show a month of entry data in a simple and accessible way using a calendar format.

The federal courts provide an educational resources page explaining the difference between opening and closing which states: “Although opening statements should be as persuasive as possible, they should not include arguments.” To create a persuasive opening, you will need to come close to argument so the jury understands why your witnesses and exhibits matter. Write your opening with your closing in mind.

Practicing delivery of an opening or closing before an audience will improve the presentation.

Standing up and speaking differs greatly from just writing what you will say. Your heart rate goes up. You get nervous, and your voice may falter. You may stumble over names. You need to check your notes too much. You will decide to change things because they don’t feel right when you say them. You begin to understand how long your presentation will take. If you have visual aids (which you should), you need to make transitions and introductions.

My partner, Morgan Smith, and I are former trial attorneys, so we often help clients practice openings and closings and we provide suggestions. We can also provide additional help such as:

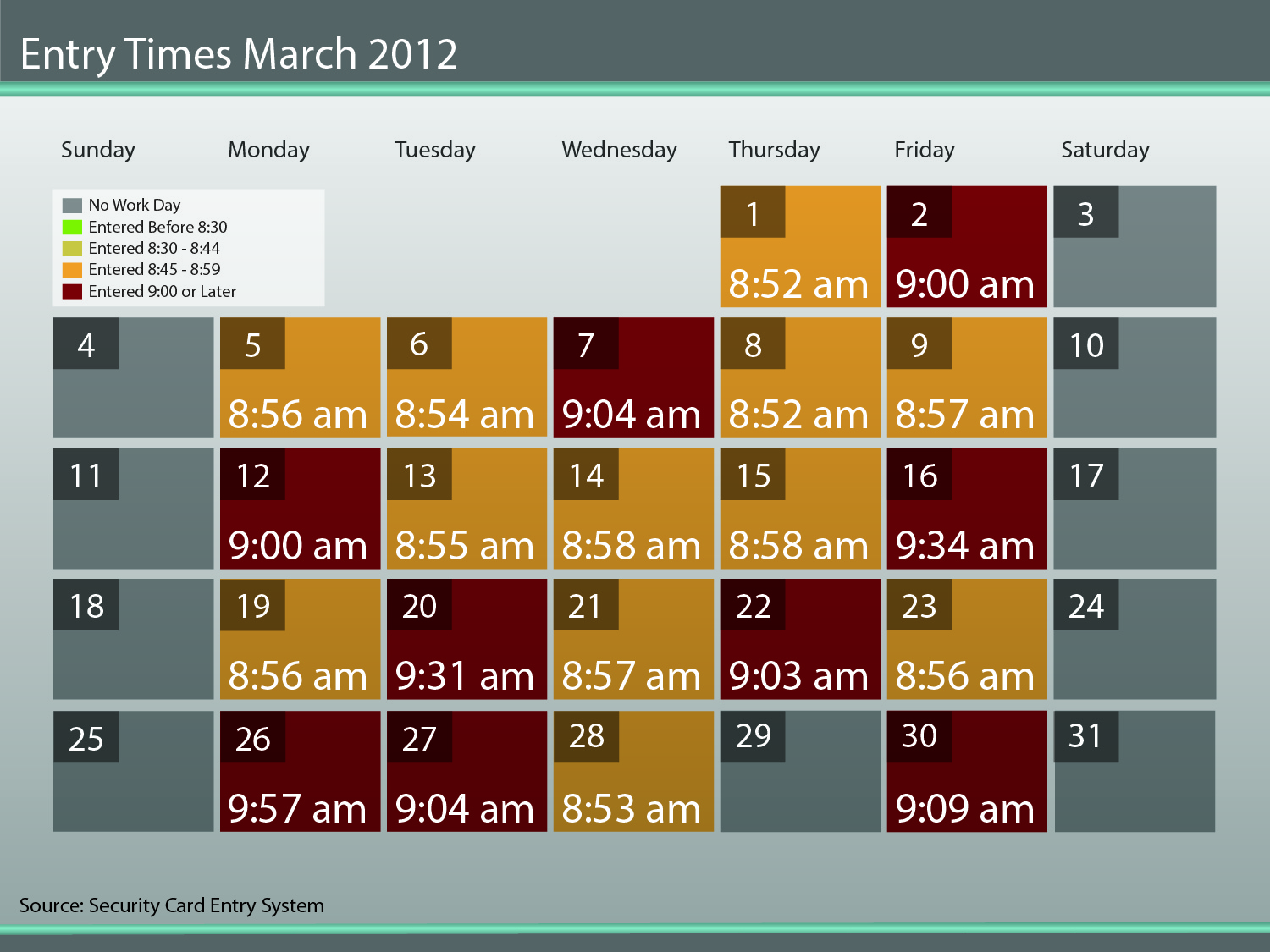

Visual information helps our brains process and understand concepts in many ways:

Improved Retention : As set out in a Department of Labor study on effective presentations , combining oral and visual information increases audience retention significantly.

Improved Persuasiveness : Visuals have been proven to improve the persuasiveness of your courtroom presentation (see Statistical Proof that Legal Visuals Work to Persuade Jurors).

“Truthiness” : Images cause us to make unconscious associations, and these associations can help persuade. For example, a picture of hands shaking is often used when attorneys talk about contracts. This image does not prove a contract existed, but it can help persuade a juror nonetheless. Of course, you need to avoid being misleading, and also know that using a non-probative image can open your graphic to attack from the other side (e.g., “Remember that picture of hands shaking that you just saw? It’s a stock image that you can find on the internet. My opponent showed you that picture because there never was a handshake like plaintiff would like you to believe.”) (For more, see Morgan Smith’s post Don’t Let Your Trial Graphics Go Beyond Advocacy to Misleading, and this article on truthiness.)

Engage Visual-Learner Jurors : According to a study by MindTools, 65% of all people are visual learners.

Jurors Expect On-Screen Information : Jurors are accustomed to high-quality video information from television, the internet and other sources. Researchers at Ball State University’s Center for Media Design reported in 2009 that adults in the US are exposed to media screens of one kind or another on average about 8.5 hours per day. If you want to connect with jurors accustomed to screens, make your in-court presentation visual.

Presenting visually does not mean putting bullet points or big quotes on the screen for your jury to read. Large blocks of text on the screen distract your jury. Jurors read faster than you can speak, so they’ll quit listening to you, and read the screen. When they’re done reading, they’ll likely tune you out again because they think you are just going to repeat what they read. Moreover, you’ve split your jurors’ attention and made it harder for them to understand what you’re saying.

When done well, visual presentations reinforce and supplement your argument, often with information that is difficult to convey with spoken words. For example, a map or diagram of the scene helps the jury understand spatial information. Moreover, a visual display can make your spoken presentation more interesting because you can control the display to direct the jury’s attention (e.g., by highlighting, zooming in, gesturing, etc.).

When You Need to Show Text, Do It Well : Of course, text often has a place in the graphics for an opening or closing. For example, you may need to show the jury the key language from a contract, or show what a patentee said during prosecution of a patent. When you do show text, avoid the pitfalls that will bore and turn off your jury. In particular, think about the following tips:

Preparing a good opening or closing takes time, particularly when you want an engaging visual presentation. While it is possible to scramble to create something within a few days, you can do much more if you start with two or more months of lead time. Starting to see visuals will give you new and better ideas for what else would be helpful, and you can do that if you have built in enough time.

If you’d like to receive updates from this blog, please click to subscribe by email.